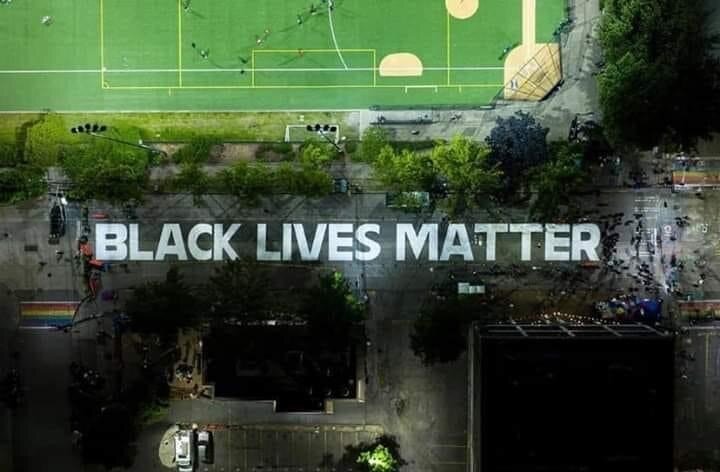

Letters from the CHAZ / CHOP

Photo: Erika Schultz / The Seattle Times

“What are you doing here?!” His muffled scream rushed through his mask.

His face was already red with rage, the veins around his temples beginning to bulge, a fury written across his eyes.

“Are you just here to continue to perpetuate the stereotype that Christians are willfully spreading around the country, that we’re some sort of godless, anarchist playground? Are you here to destroy our protest as a wolf in sheep’s clothing?!”

This wasn’t the first time, nor the last time I’d encounter someone angry with my presence that evening. But it was certainly the loudest.

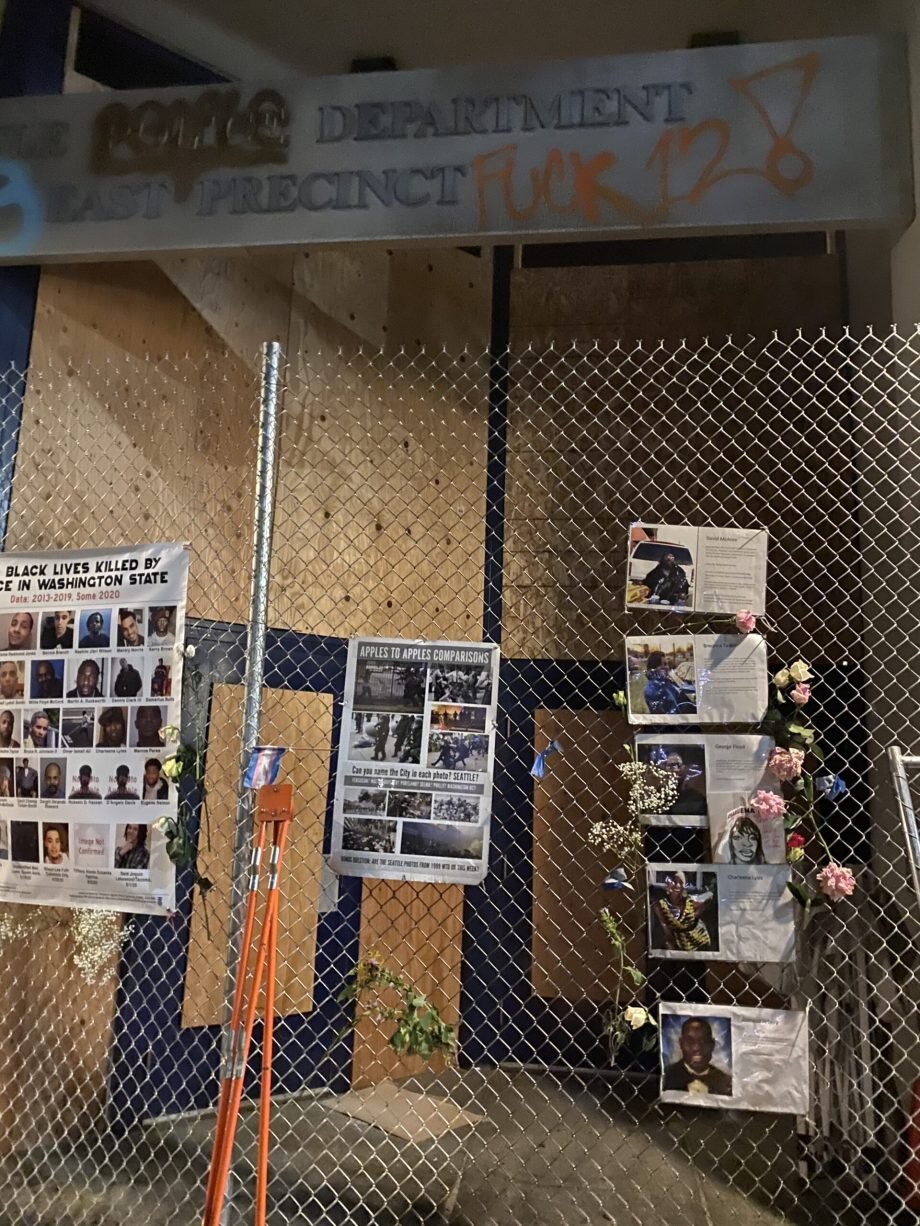

I’ve been serving as a protest chaplain in shifts with a group of other religious leaders from Seattle. We stand by a meager table with a sign that simply reads ‘Interfaith Chaplain’ offering masks, hand sanitizer, candles for the growing memorial by the police precinct, prayer, support, conversation, blessings, and anything else someone may need to feel cared for in this space.

Often times I’m asked to provide insight, attributing spiritual significance for what’s happening in the nearly 6-block protest zone, many of whom are simply struggling to find the right words or context.

As you look around this active protest, in many ways it resembles a street fair. Children are running around—a few with painted faces—a hot dog vendor sets up on the corner, there’s a stage in front of the police precinct where spoken word poets, bands, impromptu speakers, and organizers share their points of view. Trash teams are deployed for garbage and recycling duty, a large food co-op tent hands out freshly made meals, water, and other hygienic items. A de-escalation team working to diffuse tense situations as performance-based counter protestors and agitators make their way in a few times each day and a medical tent is set up to provide care, and not just physical care but mental care as a team of trauma counselors care for those traumatized by what has taken place. Many are still reeling from the use of tear gas and flash bangs that made the intersection look like a war zone, while others are wrestling with anger, fear, and confusion after a car plowed into the crowd of protestors, the driver shooting one of the men who tried to stop him. This, by the way, is why there are barricades on the streets now: to protect the people from those who seek to do harm.

On Saturday night I was situated with a rabbi inbetween a clothing co-op and a voter registration drive. Across the street sat a table, “Write Mayor Durkan” and next to them a black artist set up an easel to paint. The space is filled with opportunities for direct action, ways to create specific and lasting change within our city.

Seattle has had a long and strained relationship with the police department. For the better part of a decade, the Police Department has been under a consent decree for civil rights violations. And for the better part of a decade, the Seattle Police Department has failed to live up to that consent decree, with the police union finagling ways to get out from underneath it without ever fully complying. Community trust has been broken, and every act is now seen through a lens of suspicion.

He continued to yell at me, spouting every sort of hateful idiom towards Jesus and the Church that he could muster. His anger was filled with a deep, deep pain. His rage lasting for a couple of minutes. And as he drew his last deep breath, he finished with a giant, “FUCK YOU!”

I paused to take a breath.

“Did you get it all out?” I gently, and lovingly replied.

“What?” His eyes softened a bit; anger replaced with confusion.

“This is what I’m here for. Did you get it all out?”

“Wait. What?”

“If you have more that you need to say, I’m here to listen.”

His eyes darted back and forth with confusion. “I mean… what?”

“I get it. I get your anger. I’m mad too. There are so many false stories and narratives surrounding this space and what it is. So many lies about what has happened here, what is happening here. I’m angry too. I see what this place is and what it has become. I’ve been here a lot over the past few days, and I know what it is and what it isn’t.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. I understand your anger.”

“Will you tell our story? Will you share with other Christians what’s happening here and dispel the lies?”

“I’m trying to.”

Over the past several days I’ve been interviewed by Politico, the Seattle Times, Sojourners, a myriad of Twitch feeds and Facebook Live posts, even Japanese Television sent an anchor to do an interview. All in an attempt to understand what the space now known as the CHOP (Capitol Hill Occupied Protest), actually is.

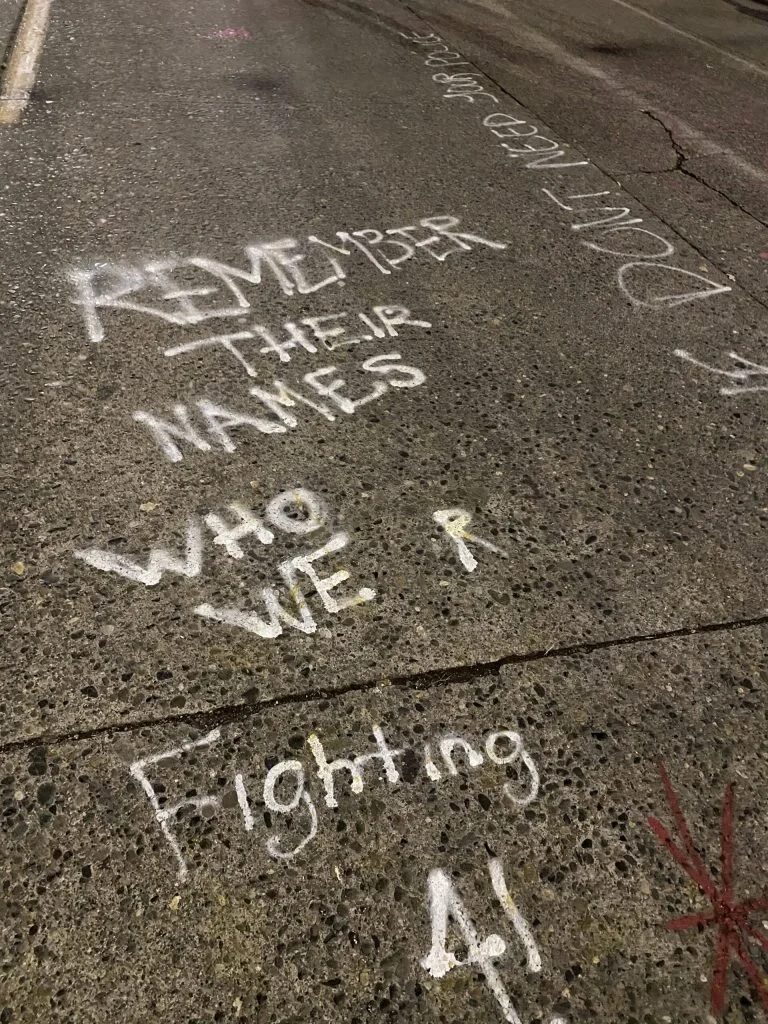

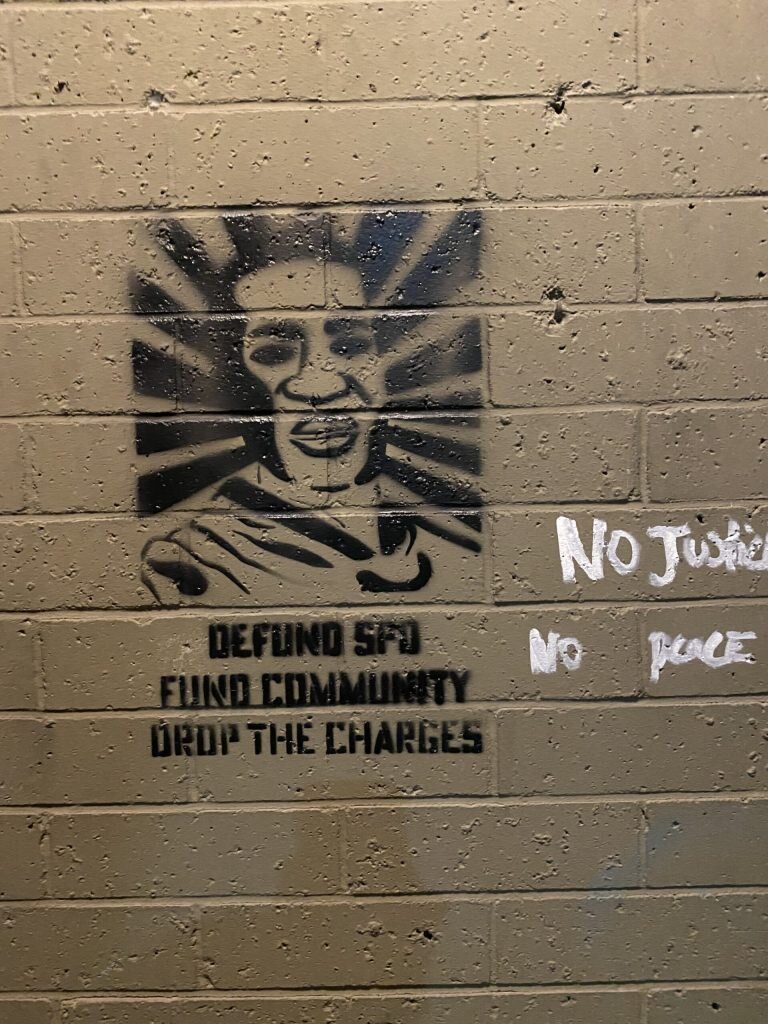

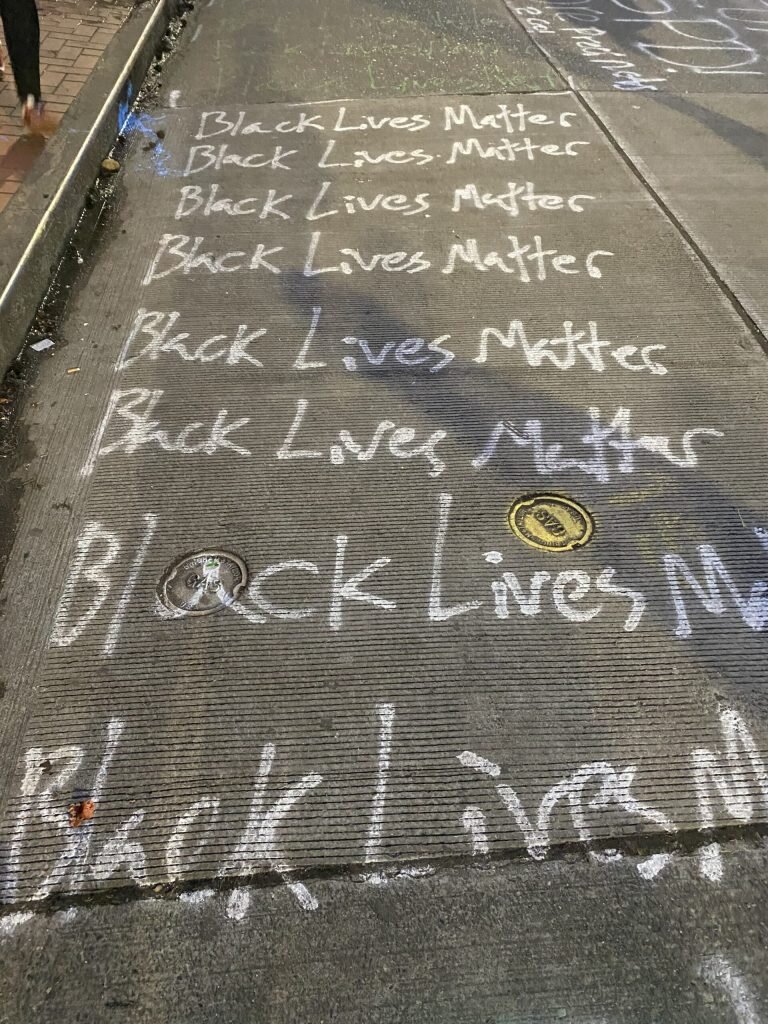

Over and over I have reiterated the same story using familiar religious language. This space is a shrine. It’s a shrine to the deep seated anger and pain, the overwhelming grief and lament that is being felt by the people. Throughout the area, there are prayers written on the ground and on signs, laments and grief and anger scrawled on signs hanging from fences and buildings, memorials and vigils erected for people who have been lost in Seattle to police violence—the list is not short. This has become an Ebenezer stone of sorts with the east precinct of the Seattle Police Department the centerpiece. This has become, for many, holy ground.

Ed Stetzer exhorted Christians to be more careful with what we post online, to verify and fact check what we say before we become false witnesses and thereby damage our credibility and Christ’s message. You now have a first-hand witness, and multiple accounts of what is actually happening in the CHOP. I am making myself available to you: Ask me anything and I’ll share more with you, or I can find out the answer. But please stop spreading and bearing, knowingly or unknowingly, false witness. You are damaging the credibility of the church in Seattle. The CHOP is not what you may think it is.

On Monday night a man set up a speaker and a microphone in the middle of the intersection by our table. A group of 6 were playing basketball at a hoop on the corner that had appeared earlier that day. “I have a question.” His deep, booming voice echoed through the crowd. People stopped, and gathered around. “I have a question I want to ask you all. What does Black Lives Matter mean to you?”

A couple of his friends worked to organize a line and one by one people stepped to the mic to share. About 15 minutes in, the crowd had grown to well over 1000 people when a black man stepped up and held the mic. “Jesus,” he started. “Jesus was a non-violent revolutionary who told the world of love. Who demonstrated that love for us on the cross. He told us to love our neighbor, but also to love your enemy!”

A smattering of applause, a couple of ‘Amens!’ and jeers co-mingled and rose from the crowd. “This right here,” he continued, “is a non-violent revolution of love in the name of Jesus. And Jesus knows what it means to suffer. Jesus knows the pain we’re feeling right here. He too was an oppressed minority, suffering under the weight of the systems and structures that murdered him and his people. He resisted. But he did it in the name of love. This right here is a non-violent revolution of love in the name of Jesus!”

All lives cannot matter until Black lives matter.

Whether or not you agree with the tactics of the protestors, whether or not you feel as if this is an affront to you personally or your political persuasion, I need you to know that Jesus is in that place. And he is at work.

Photo: Rev. Mindi Welton-Mitchell

A couple of nights ago, three Jesuit priests from Seattle University (a Jesuit school a few blocks from the CHOP) stopped by. “We’ve been looking everywhere for you.” They said. “We were just lamenting the fact that there was no spiritual guidance or presence in this place. Seeing you all here brings us such joy, may we join you?” As they pointed to the streets filled with the people one of the priests wistfully waved his hand over the crowd: “Can’t you see it? Can’t you just see the Holy Spirit moving in this place and among the people?”

“I can now,” I thought to myself. “I can now.”

I hope you can too.

A reflection on the Capitol Insurrection of January 6, 2021 that was delivered for United Church. It was written as a diagnosis of what plagues the white Evangelical Church and a prescription for healing and change.